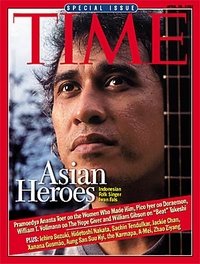

Former Indonesian

Former Indonesian ruler Suharto died last month a very wealthy man. In 1999, a year after he stepped down as Indonesia's second president,

Time magazine reported his wealth at US$15 billion.

"Not bad for a man whose presidential salary was $1,764 a month when he left office," the magazine reported.

And not bad for a peasant boy born in 1921 in Kemusuk, a small Javanese village, during Dutch colonial control. Suharto's route to power and wealth was through the military. In 1954, he took a new job in Semarang, on the north coast of Java, only a three-hour drive from his military base in Jogjakarta. It thrust the 33-year-old Javanese officer into a totally different world.

Before the 1954 promotion, Suharto had been a field commander. Now, as head of the Diponegoro military command in Semarang, his immediate job was not to lead military operations, but to feed the thousands of troops under him. His new division consisted of an assortment of thugs and soldiers, bandits and militias. And like most post-independence armies, it was poorly funded.

If Suharto was to succeed in the new Indonesia that was emerging after World War II, he would have to find ways to keep the army in food and equipment. He looked to the example of his wife, Siti Hartinah. Although she came from Javanese aristocracy, she was supporting the family, which already had three young children, with the small garment trade she had started.

Suharto, too, turned to business -- mainly smuggling such consumer goods as sugar and rice between Singapore and Java. He defended running a business out of the army as essential to feeding his men.

Key to his operations from the start were two men who would remain his business associates for almost half a century. Suharto's tie to Liem Sioe Liong, a Fujian-born Chinese merchant who had migrated to Java in 1938, was to become one of the most important alliances in his New Order regime. Suharto also befriended sportsman-cum-businessman Bob Hasan, whose godfather was an army general.

The relationships were mutually beneficial. Suharto used his troops and position to protect the lucrative smuggling; Liem and Hasan helped supply the troops and provide Suharto with business opportunities.

According to George J. Aditjondro, a corruption researcher who spent two decades tracing the Suhartos' fortune, Suharto basically built his "business model" in the city of Semarang and gradually expanded it, enlisting other officers and businessmen along the way.

In 1956-1957, his Diponegoro operations came crashing down. Suharto was found guilty of smuggling, and army head Colonel Abdul Harris Nasution tried to remove him. But Bob Hasan's godfather, Colonel Gatot Subroto, defended his protégé. Army headquarters defused the scandal by sending Suharto to an officer-training program in Bandung, in West Java.

Within two years, he bounced back, won another promotion, and took command of the Kostrad army reserve in Jakarta. The problem of supplying troops remained the same, as did Suharto's solution of choice. He bought his business partners along with him to Jakarta.

Suharto's political career took another turn on September 30, 1965, when hundreds of army officers kidnapped and killed several generals. Suharto knew of the plan in advance since most of the kidnappers were his Diponegoro colleagues. They reportedly planned to bring the generals, including Nasution, who had allegedly planned a coup, to face President Sukarno.

The next day, Suharto decided to move against his former colleagues. Blaming the communists, his troops began a slow purge against Sukarno, Indonesia's first president. The ensuing maelstrom of violence killed three million people between October 1965 and March 1966, according to one of his officers, Major General Sarwo Edhie Wibowo.

By 1968, at 47 years old, Suharto had emerged as Indonesia's number one man. He sidelined Sukarno and ruled the country with an iron fist for the next 30 years.

Human RightsSuharto has been accused of a wide variety of human rights abuses. In 1975, he ordered his troops to invade East Timor. The estimated death toll included up to 200,000 East Timorese, 100,000 in West Papua, and tens of thousands more in Aceh, Lampung, Tanjung Priok, West Kalimantan and elsewhere. Even while partnered with Liem and other Chinese tycoons, he systematically discriminated against the Chinese minority in Indonesia. The East Timor Action Network, a New York-based human rights group, called Suharto, "one of the worst mass murderers of the 20th century."

In his official biography, Suharto admitted that in 1983-1984 he had ordered "mysterious shooters" to kill between 2,000 and 3,000 thugs, thieves and robbers. This "shock therapy," as Suharto called the killings, earned him the nickname "Gali Pelarian Kemusuk" or "The Thug from Kemusuk."

Joining Thuggery and ProfitsBut Suharto was no ordinary thug. He was a business-minded one. Between 1971 and 1972, he and Liem set up giant wheat flour manufacturing plants. PT Bogasari Flour Mills, the foundation of Indofood, is now the world's largest instant noodle manufacturer. Liem also set up Bank Central Asia, one of Indonesia's largest private banks, in which Suharto's children owned shares.

Throughout his rule, Suharto has been implicated in systemic corruption and cronyism that distorted Indonesia's economy. When the economy boomed in the 1970s, along with increased oil prices, Suharto ordered his U.S.-trained economic ministers to issue regulations that included deducting small amounts of money from the salaries of civil servants for charity. The "donation" was automatically channeled to his Supersemar Foundation and Dakab Foundation and some of the funds did help the poor, provide student scholarships and build mosques. Suharto's Dharmais Foundation established one of the biggest cancer hospitals in Jakarta.

But from the 1980s, the recipients of the charity also included Suharto and his cronies who invested the money in dozens of companies. Later, his economic ministers issued regulations that granted monopolies to favored companies. Liem won government contracts to supply wheat flour and cloves. Hasan won millions of forest concessions and won the nickname "Raja Hutan" or "King of the Jungle."

George Aditjondro, who has tracked the family’s fortune, wrote that Suharto established at least 40 foundations since the 1950s. The family owned shares in large companies, including in the cement and fertilizer industries, toll roads and oil palm plantations.

In the late 1980s, when Suharto's six children came of age, they joined the business, helped by "Uncle Liem" and "Uncle Bob." Hasan joined with Suharto's eldest son, Sigit Harjojudanto, to set up PT Nusantara Ampera Bhakti, a holding company in mining and telecommunications. Supersemar, Dharmais and Dakab also own shares.

The middle son, Bambang Trihatmodjo, established ties with the army-owned Kartika Eka Paksi Foundation, and shared ownership with Hasan in his international timber corporations. Hasan’s paper mill, PT Kiani Lestari, received funds from Suharto's foundations. The youngest son, Hutomo Mandala Putra, also linked up with a Hasan operation, Sempati Airlines. When Suharto's wife died in 1995, "Uncle Bob" became Suharto's main advisor on the children's businesses.

Demands For Prosecution By the time Suharto finally stepped down from power in May 1998, he was facing street protests and the Asian economic crisis. The value of the Indonesian rupiah against the American dollar fell from 2,300 to 10,000. Many civil society organizations demanded that his successors prosecute Suharto and his cronies for criminal corruption.

M. Fadjroel Rachman, a former political prisoner who campaigned for prosecuting the Suhartos, said that the government should take over the Suhartos’ fortune. Rachman especially targetted the former president’s six children and one grandchild: Siti Hardiyanti Rukmana, Sigit Harjojudanto, Bambang Trihatmodjo, Siti Hediati Harijadi, Hutomo Mandala Putra, Siti Hutami Endang Hadiningsih and Ari Harjo Wibowo. Ari is Sigit Harjojudanto's son, and Suharto's eldest grandchild.

The family was protected not only by its vast wealth, but also by the network of cronies that also benefited from the Suharto fortune. Michael Backman, a researcher and business analyst in Asia, once calculated the Suhartos owned 1,247 companies. A May 1998

Asian Wall Street Journal article reported that these companies were owned by at least 20 different conglomerates, including Liem's Salim Group and Hasan's Kiani Lestari Group.

Time magazine researched land ownerships and reported the Suharto family, on its own or through corporate entities, controlled some 3.6 million hectares of real estate in Indonesia -- an area larger than Belgium. That includes 100,000 square meters of prime office space in Jakarta and nearly 40 per cent of the entire East Timor.

No one knows how exactly much wealth the Suhartos accumulated. Family lawyers and children repeatedly denied allegations of vast wealth and Sofyan Wanandi, a businessman once closed to Suharto, said that the family had lost much of its fortune because of mismanagement and the weakened rupiah.

When

Time magazine estimated the Suhartos' wealth at US$15 billion -- of which $9 billion had been transferred from Switzerland to a nominee bank account in Austria -- Suharto denied the report. He insisted that he had no bank deposits abroad and owned only 19 hectares of land plus $2.4 million in savings.

In 1999, Suharto filed a lawsuit against

Time magazine for defamation. After a nearly a decade of legal battles, Indonesia's Supreme Court ordered Time to pay $106 million in damages.

Time and its reporters refused to pay.

A family lawyer, Juan Felix Tampubolon, told the London-based

Financial Times that he had no idea how rich the Suharto children were. "Yes the children have companies but, as far as I know, these are legal," he said. "All the accusations are merely that. There are newspaper clippings but no proof."

Nonetheless, in 2004, Transparency International, an anti-corruption watchdog, named Suharto the world's greatest ever kleptocrat and put his fortune at up to $35 billion. The United Nations and the World Bank quoted this research when they launched an international campaign last year to help governments recoup state assets stolen by previous regimes.

Efforts To Regain The Wealth Over the years there have been repeated efforts to recoup the money that critics claim Suharto stole from his country. In 2007, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono's administration filed a civil suit for US$1.54 billion against Suharto and one of the seven major foundations he established. State prosecutors alleged he had stolen $440 million from the government.

But even from beyond the grave, Suharto wields influence and loyalty. When he died in January at 86, President Yudhoyono immediately cancelled a scheduled appearance at a UN conference on retaking states' stolen assets. Instead, he went to the Suhartos' mausoleum to preside over the patriarch's burial ceremony. Like most Indonesian leaders, Yudhoyono was a Suharto crony. And like his predecessors in office since 1989 -- B.J. Habibie, Abdurrahman Wahid, and Megawati Sukarnoputri -- he was unlikely to be able to retake the stolen assets.

Vice President Jusuf Kalla, who repeatedly asked for a pardon for Suharto, owned businesses that thrived during the Suharto rule, according to Rachman. Kalla is currently chairman of the Golkar Party whose chief patron was Suharto.

Last year Kalla tried to protect Suharto's youngest son, Hutomo Mandala Putra, after his money was frozen in a BNP Paribas account in the popular offshore haven of Guernsey, UK. Yudhoyono and Kalla are only two of Suharto's many cronies still in power. And hundreds, perhaps thousands, of military officers, politicians and business leaders remain loyal to the family.

But critics like George Aditjondro and Fadjroel Rachman doubt that the country's leaders have the political will to follow the money trail. Retaking the stolen assets, said Rachman, will take place only "when the young leaders of Indonesia replace the Suhartoists or the old leaders like SBY, JK and their generation."Suharto and most of his circle escaped unscathed and rich. Suharto was never prosecuted. The public reason was that in 1999 doctors declared him too unhealthy to stand trial. But critics say the real reason is that successive administrations are still highly influenced by Suharto's henchmen and cronies.

Only one family member, Hutomo Mandala Putra, nicknamed Tommy, was prosecuted for corruption. He was convicted but acquitted on appeal. He is now facing a civil suit as part of a government bid to recover millions of dollars from Garnet Investment Limited that has been frozen by BNP Paribas. Tommy also spent four years behind bars for hiring hitmen to kill Supreme Court Judge Syafiuddin Kartasasmita. The judge had convicted Tommy for corruption and illegal possession of weapons. Hasan spent three years in prison for causing a US$244 million loss to the Indonesian government through a fraudulent forest-mapping project in the early 1990s.

The military's involvement in business also continues, prompting critics to ask if they are businessmen with weapons or soldiers with check books. In June 2006, New York-based Human Rights Watch published a 126-page report,

Too High a Price: The Human Rights Cost of the Indonesian Military’s Economic Activities, describing how the Indonesian military raises money outside the government budget through a sprawling network of legal and illegal businesses. Working with many business partners, the military has provided paid services, marked up military purchases, and invested in hundreds of companies.

Today Suharto is dead, Liem is living in Singapore, and Hasan is semi-retired in Jakarta where he plays golf. But the business model the three partners built in Semarang in the 1950s endures and still forms the pillars of the Indonesian economy. Whether or not anyone has the will or ability to undermine this corrupt and intertwined edifice is a question that is crucial to Indonesia's future.

Corp Watch is a San Francisco Bay Area-based non profit organization that has been educating and mobilizing people on human rights abuses by multinational corporations. Founded in 1996, it was initially known as TRAC (Transnational Resource & Action Center) with a website called Corporate Watch. In March 2001, it simplified the situation by using one name, one logo and a matching website address: CorpWatch.